Because you’re worth it.

Written back when it was fashionable to make Excel do strange things.

(Disclaimer: Uses Windows Timers. Probably doesn’t work nowadays. Will spoil your milk, make strong men weep, and turn the weans against you)

At some unspecified time in the past, when I was in a managerial/quasi-managerial role in an investment bank (keep it vague, Matt, keep it vague), we had An Occasion when anyone who was managerial/managerial-adjacent was brought into a half-day session organised by HR about how to deal with Millennials. The reason? We were having a lot of problems around retention for graduate Millennial joiners in our most recent year group, and we wanted to stop the rot.

The session covered the familiar talking points that the older generation typically raise about feckless youth. Millennials expect too much on coming into an organisation, when they aren’t ready for the responsibility. They don’t respect hierarchy. They require coddling. They’re snowflakes. And so on, yadda yadda yadda.

But I knew why the Millennials were really leaving. In the problematic year group, a few people had been placed, post-internship, with a part of the organisation that had been deemed non-profitable. They were laid off rather than places being found for them elsewhere. This was a violation of an implicit contract that this and similar organisations had at the time – while we might have a lot of churn and instability, we would not crap on people fresh out of an internship by making them redundant, no matter what. The norm would be that you would reassign them. They’ve been around for a few years? Fine, it’s open season. But less than 12 months after starting full-time work? Nope.

As a consequence of this norm violation, meerkat-like, everyone in that year’s cohort raised their heads, nodded at each other, and a decent fraction (disproportionately selected from those with most moxie and smarts) had changed their employer to be someone other than us before the year was out. They were absolutely right to have done so, and I would have done the same thing myself in their position.

I knew what was really going on because – unlike most of my colleagues in the managerial sphere at that organisation, at that time – I took pains to check in with everyone I felt responsible for on a fortnightly basis.

(Yeah, I know everyone does this weekly nowadays but this was many years ago, and we’re talking 14 people here. I was busy, OK?)

Much to my shame, I didn’t speak up during the session. I nodded along with everyone else, tutted about how terrible the Millennials were, and was working somewhere else myself before the year was out.

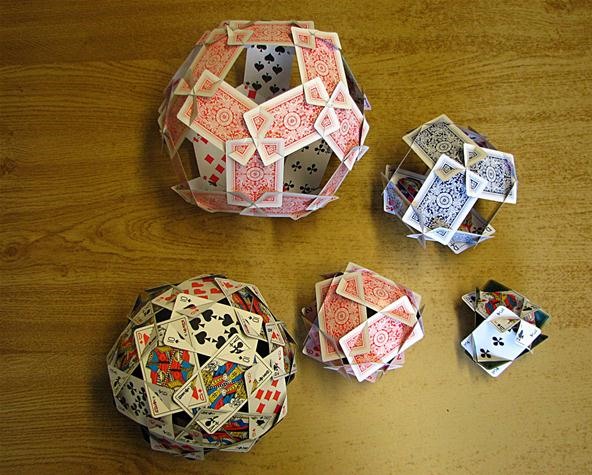

In 2011, Nick Sayers made a roughly spherical design out of 270 playing cards. Well, 265 if you leave a hole to put a light-bulb in – 5 whole decks, plus one joker from each. It’s easy to find pictures of it on the internet, e.g. here and here. It has gaps to allow light through. It has a pleasing mixture of structure and irregularity. It looks fantastic. I wanted to figure out how to make it myself.

The design looks complicated, but it’s not so bad. It’s a Platonic solid in disguise – either a dodecahedron or an icosahedron, depending on what you say the centre of the face is: from the angle of the playing card cuts, it’s pretty much a wash since everything bulges outwards a bit, compared to a true Platonic solid.

You can figure out how to fit the cards together from the pictures (whether of Nick Sayer’s build or mine). But before getting started on this, I highly recommend you figure out how to make some Platonic solids first – it’ll give you an idea of how this kind of thing works. See my previous post for more on that.

Assuming you’ve gained some basic idea of how to build the simpler stuff, then here’s the key to building the 270-card behemoth: there is a 9-card motif that you need to repeat 30 times, which is shaped like a diamond. At each of the two sharp points of the diamond , 5 cards come together. At each of the other two points of the diamond, 3 cards come together. Everywhere else, 4 cards come together.

The really interesting bit is exactly where to cut the cards so they slit together in the right way. On my previous post for building Platonic solids, you can see how this kind of thing gets worked out. For the 270-card construction, by all means work out a theoretical starting position (this helped me) but eventually you will need to be prepared to experiment with a pack or so of cards to see what alternatives pan out best given the way the physical material behaves. I recommend using packs of Waddingtons No. 1 cards when experimenting – they are pretty tough and nice and cheap.

(Note that each 9-card motif uses 5 cards with one pattern of cuts, and 4 cards with the mirrored version. )

In terms of actually putting it together, build one 9-card motif off to one side, and refer to it as you make the main build. Start with a 5-vertex and build outwards from there. Once you have all the slots cut, and any other backing applied (see below), it will still take you at least 4 hours to put everything together. There are some points where you can take a rest – basically you’ll need to complete something radially symmetric so it doesn’t start bending too much.

While a finished build looks great, it does have one drawback as a lampshade: playing cards are not designed to let light through – it’s kind of a major part of their job description, come to think about it. So, while the lampshade does look lovely with a light bulb in the middle, it’s somewhat underpowered as a light source: more of a glowing coal than a blazing fire, let alone a UFO that will eat your mind as you gaze dumbly into its alien projection of Nirvana.

Sorry, where was I?

Ah, yes: improving light output. I did wonder if it might be possible to get more light out by building it with cheaper playing cards, which lack the “core” that makes normal playing cards opaque. But such cards tend to be generally weak, whether from the lack of the “core” layer or just because the cardstock is thinner. This weakness rules them out: the twisting inherent in the design means that those cheaper cards rip and can’t be used successfully.

My best idea so far: put stick-on chrome mirror vinyl on the parts of the backs of the cards that lie entirely within the construction: the idea being that the light will bounce around until it eventually makes its way out. From the outside, it still looks like normal playing cards – but now, when you chuck light out from the inside, you now get more than just a gentle glow – enough light escapes to get some general illumination of the surrounding space. An encouraging sign is that the colour of the light that escapes is a closer match to the original bulb colour – before, it took on the hue of the playing cards, since so much of it was being absorbed by their surface.

More external light would still be good. The photos below are all I currently get from a 26W corn led light bulb, which puts out 3,000 Lumens (around 200W equivalent for an incandescent) so is already quite punchy. I’ll try ramping it up and see how far I can go before setting everything on fire.

As to which playing cards to use? The main problem is potential tearing where the cards meet – once the whole construction is made you’re fine, but while putting things together you can end up with quite a lot of stress being put present at some stages. I prototyped with Waddingtons No 1 bridge cards, only £1.40 a pack, and they stood up to the twisting forces involved remarkably well. The final build uses Compag Jumbo Index Poker Cards, which are more like £10 a pack in the UK: about as resilient as you are going to get. But to be honest, they didn’t really deal with the forces much better than the Waddingtons did – although I did dial up the amount of card twisting to the maximum level I thought I could get away with.

Yet another very niche post. Would you like to do this?

This image is taken from https://mathcraft.wonderhowto.com/how-to/make-platonic-solids-out-playing-cards-0130512/ – however the templates document that this page refers to is no longer available, and there’s no information on the underlying maths either.

I’m trying to figure out how to build more complex stuff of this type, so I figured it was worth sitting down and working it out from scratch. See below for both the maths, and the cut angles for all 5 platonic solids.

There are a number of ways to go

I’d like to explore the textual side, but it’s hard to bridge the gap between text and drawings, integrating them effectively. I feel like it’s maybe going to be the best to explore though, as the other territory seems to be thoroughly colonised. The counter-argument is that I think that Cy Twombly sucks ass.

One possibility would be to extend the non-line nature of text into collage?

This the concluding part of a longer essay I wrote a while ago, when sorting out my thoughts on anti-vax. It’s based on “The First Rotavirus Vaccine and the Politics of Acceptable Risk”, Milbank Q. 2012 Jun; 90(2): 278–310.

(Context: there was a “RotaShield” vaccine withdrawn in 1999 following confirmation of a serious adverse event associated with its use with infants. The story around this is an important part of the mythology of anti-vax in respect to one of their prime targets, Paul Offit – one of the most public faces of the scientific consensus that vaccines have no association with autism, among many other things)

The history of the Wyeth/RotaShield vaccine’s approval while Paul Offit was on the ACIP panel is crucial It is at the heart of disagreements around Offit himself, but it also operates as a key part of a negative feedback loop that poisons discussion across the pro-vaccine/vaccine-sceptic divide. I will explain why.

The pro-Offit position is that everyone made decisions around Wyeth/RotaShield in good faith, and that the decisions made remain perfectly understandable based on the evidence available at the time the decisions were made, and that there is no evidence to support the notion that there was wrongdoing involved.

I believe that this position is true.

I simultaneously believe that the ACIP process at the time needed improvements to its conflict-of-interest policy. The very fact that people can accuse Offit over RotaShield in the way they do, in a manner that carries a reasonable degree of credibility to a casual observer, surely proves that there is an issue here. I do not think there is any inconsistency in holding these two beliefs at the same time: you can believe that a COI policy needs improvement, without believing that people in any given situation in fact acted badly.

But Offit’s hard-line critics see a very different picture. They see someone who joined the ACIP panel primarily to enrich himself – using the influence of his position to create a vast and open market for his own (Merck/RotaTeq) vaccine by rushing through the approval of a competitor (Wyeth/RotaShield) vaccine with known safety issues. At its strongest, the narrative is that Offit was fully expecting RotaShield to be withdrawn, leaving the pre-established market wide open just as his own vaccine was available to fill the gap. The consequence of this was the suffering of around 100 children, of which 1 actually died and 50 had to have surgery. In return for this, he has profited to the tune of tens of millions of dollars.

In other words, the essential narrative for many of Offit’s opponents is that he has killed a child for money – that Paul Offit is literally a baby-murderer.

Everything else in people’s views of Offit flows from their interpretation around the RotaShield episode. To call this an “interpretation gap” is a huge understatement: it is a gulf, a chasm. It is impossible to reconcile the views. Offit is a medical researcher who has saved hundreds of lives. He has killed a child for money. He campaigns energetically to save lives in the face of death threats. He schemes endlessly to further his own interests, while children suffer and die as a direct consequence. He is a good man who is doing is best to do good things. He is “the devil’s servant” (whale.com).

And standing on the other side of the divide is Offit’s dual, the closing half of the feedback loop – Andrew Wakefield. The anti-Offit characterisation is echoed in many of the accusations that are flung at Andrew Wakefield by the more intemperate pro-vaccine parties. Truly, many from each side honestly believe that the other side’s prophet is a baby-murderer. This is such a deeply unpleasant thing to consider that the more decent among those on each side rarely articulate it openly – they don’t even like to call the thought fully to mind – but the thought is there on both sides all the same.

Both Offit and Wakefield give a lot of speeches, but they don’t use this kind of rhetoric directly about their opposite number, and there is a good reason for this. It is a deeply primal, a tremendously powerful thing to accuse someone of – there is so much energy to be tapped from the sense of revulsion that results. But it never ends well, because the energy is diseased, tainted at its source. Once you believe someone is a baby-murderer it is hard to even think of them as fully human. Discussion turns ugly even if the underlying accusation is never fully brought to the surface – the unspoken thought poisons everything that it touches, killing respect and goodwill.

More generally, it is healthy for all of us to reject accusations like this wherever they crop up, whoever they are aimed at. No monsters here – only us.

This is possibly the most obscure post I will ever write.

Having recently built a “4xidraw” as per Misan’s instructable at https://www.instructables.com/4xiDraw/ I’ve been investigating various uses: I would totally recommend this as a project for anyone into electronics. The accuracy is pretty solid, the speed is good, and the cost a fraction of the “Axidraw” from Evil Mad Scientists – although the “Axidraw” is obviously a far better buy for anyone who wants the machine to get out of the way and just get on with the art bit.

One thing that interested me was the prospect of doing full-colour images, and the “4xidraw” design seems more than capable of overlaying multiple plots in different colours. The theory here is that you combine Cyan, Magenta and Yellow in various combinations – the “CMY” part. If there’s a certain base level shared by all 3, you can draw that out into a “Key” level that is black, giving “CMYK” as the overall name. So by using 3 pens, you can potentially do full-colour designs.

However the pens that many recommend for archival quality plot prints (Sakura Pigma Microns) don’t come in CMY colours. The best we can do is “Blue” (not “Royal Blue”) for “C”, while “M” is “Rose” and “Y” is yellow. The blue, in particular, is way too dark. What to do?

It turns out that with a bit of adjustment, one can rebalance the colour to something pretty acceptable. I arrived at my mix by eye, dong test plots with a small image containing blocks with each of red, green, blue, cyan, magenta, yellow and 50% grey. Note that I only tuned colours in 10% increments. First thing to do was to reduce the “C” (blue, really) in the mix. Setting this at 50% was best – but then “Y” was slightly overpresent. Reducing that to 80% produced the best mix that I was able to come up with using Sakura colours.

I ended up with the following Python code to map from RGB to CMYK. Note that I’m always setting K to zero because, for the kind of plotting I’m doing (“wiggle plots” – where you spiral outwards and wobble back and forth by an amount proportional to the amount of colour), it doesn’t make sense to draw out colour onto a K-layer.

def rgb_cmyk_convert_sakura(r, g, b):

RGB_SCALE = 255

# rgb [0,255] -> cmy [0,1]

# white = no wiggle (0), black = maximum wiggle (1)

if (r, g, b) == (0, 0, 0):

# black

return (1, 1, 1)

rc = r / RGB_SCALE

gc = g / RGB_SCALE

bc = b / RGB_SCALE

k = 0.0 # we don't use black as this we are calculating for "wiggle" plots: here, using black doesn't make sense

c = (1 - rc - k) / (1 - k) * 0.5

m = (1 - gc - k) / (1 - k)

y = (1 - bc - k) / (1 - k) * 0.8

return (c, m, y, k)

The results can be seen below. The green of the clown’s body at the bottom right is furthest off – Sakura’s blue doesn’t really have any green in it so we are missing some saturation there. But the match overall is not too shabby.

Amaze your friends and irritate your work colleagues by setting up your own custom video background to webcam calls for a total outlay of £5!

Commercial software is out there which will attempt to extract your image and replace the background – but it’s (a) expensive to buy and (b) demanding on the processor. Far cheaper to go old-school and use chroma keying – this will enable you to use open source software to replace your background, and seems to run fine on my pre-i3 box which I got off eBay for £50 a few years ago.

1. Get Green Screen Fabric

Search eBay for “green screen fabric”. You should be able to buy 1×1.6m / 3x5ft fabric for around £5 – larger amounts will cost more correspondingly but I managed to get it working with this size.

You can jury-rig a way to hang it behind you (my own solution involves a stepladder, mop pole, g-clamp and 4 large paperclips) or buy a backdrop stand for around £20 more (search eBay for “photography backdrop stand”).

2. Install Open Broadcaster Software

This is free. Go here: Open Broadcaster Software project

3. Install the OBS-VirtualCam Plugin

This is also free. Go here: OBS VirtualCam Plugin

4. Set up ChromaKey output based on your camera feed, and make that available as a virtual camera

The basics:

Some more detailed instructions (the latter includes how to make the output available as a camera):

5. Pick your background

Both static backgrounds and videos are possible by setting them up in OBS.

We’re working our way through Corbyn and many of his supporters not being on board with representative democracy [0]. Makes it kind of tricky to work with the PLP [1]. The end-game is probably a split where you get a representative democracy party and another party based more on Momentum-style direct democracy [2]. One is likely to be a lot more effective than the other at getting things done [3].

[0] representative democracy: you elect a representative and they have autonomy once they are elected, check out Burke etc. So to say that the PLP rebels are acting against the ideals of representative democracy doesn’t really make much sense.

[1] PLP: they tend to be on board with representative democracy since that’s the water they swim in

[2] representative democracy => oligarchy. direct democracy => cults of personality and mob rule. Pays your money and takes your choice.

[3] I’ll bet my money on whichever one is aligned more effectively with the way power works in the UK political system. Which is…

I first read The Glass Bead Game more than half my life ago. The narrative centred on a quasi-monastery in a place called Castalia. The quasi-monks are devotees of the aforementioned game, which brings all artistic and scientific endeavour together in a single unified form.

I didn’t like that book at the time, and I don’t like it now. I am, at least, clearer on why I don’t like it now, for which I am sure Joseph Knecht would give thanks. Here is the difference: there is much debate in the novel over whether Castalia’s setup is effecive. But I know something that the people in the novel don’t: I know that Castalia’s setup is bad.

The idea that it is somehow always virtuous, somehow intrinsically positive, to unify diverse fields of endeavour – this idea is bad. Unification involves abstraction, and abstraction involves stepping away from the concrete world, and the concrete world is where people live, and people are the only source of meaningfulness. So you can take your high-abstraction unification and go play elsewhere.

I have spent much of my working life trying to get people to work more effectively together when tackling messy problems with a significant analytical content, and where I’ve been most successful, a key part of this success has been the mutual acceptance of multiple, irreconcilable viewpoints.

At this point I should stress I’m not some kind of weirdo anti-analytical Luddite. I love foundational mathematics, and deep connections between superficially unrelated fields (Rudy Rucker! Large cardinals! Grothendieck! Category Theory!) But around my graduation, I had the secular equivalent of a Come-To-Jesus moment. I realised that cognitive empathy was vital to me, and that this was not going to be found in sufficient quantities where I was.

So I had to start again, which was difficult for me.

I found a path that works for me. But I remain suspicious of over-eager unifiers. Although I give Derek Parfit a pass, because he winds up so many people that I find objectionable.